The Occident, And American Jewish Advocate, 1856

- Title

- The Occident, And American Jewish Advocate, 1856

- Author

- Isaac Leeser

- Date Created

- 17 June 1856

- Location(s)

- Philadelphia

- Format

- Letter. 25 page(s) on 24 sheet(s).

- Type

- Letter

- Physical Characteristics

- Lined Paper

- Manuscript

- content

-

The Occident,

AND

AMERICAN JEWISH ADVOCATE.

A Monthly Periodical

DEVOTED TO THE

DIFFUSION OF KNOWLEDGE ON JEWISH LITERATURE AND RELIGION

EDITED BY

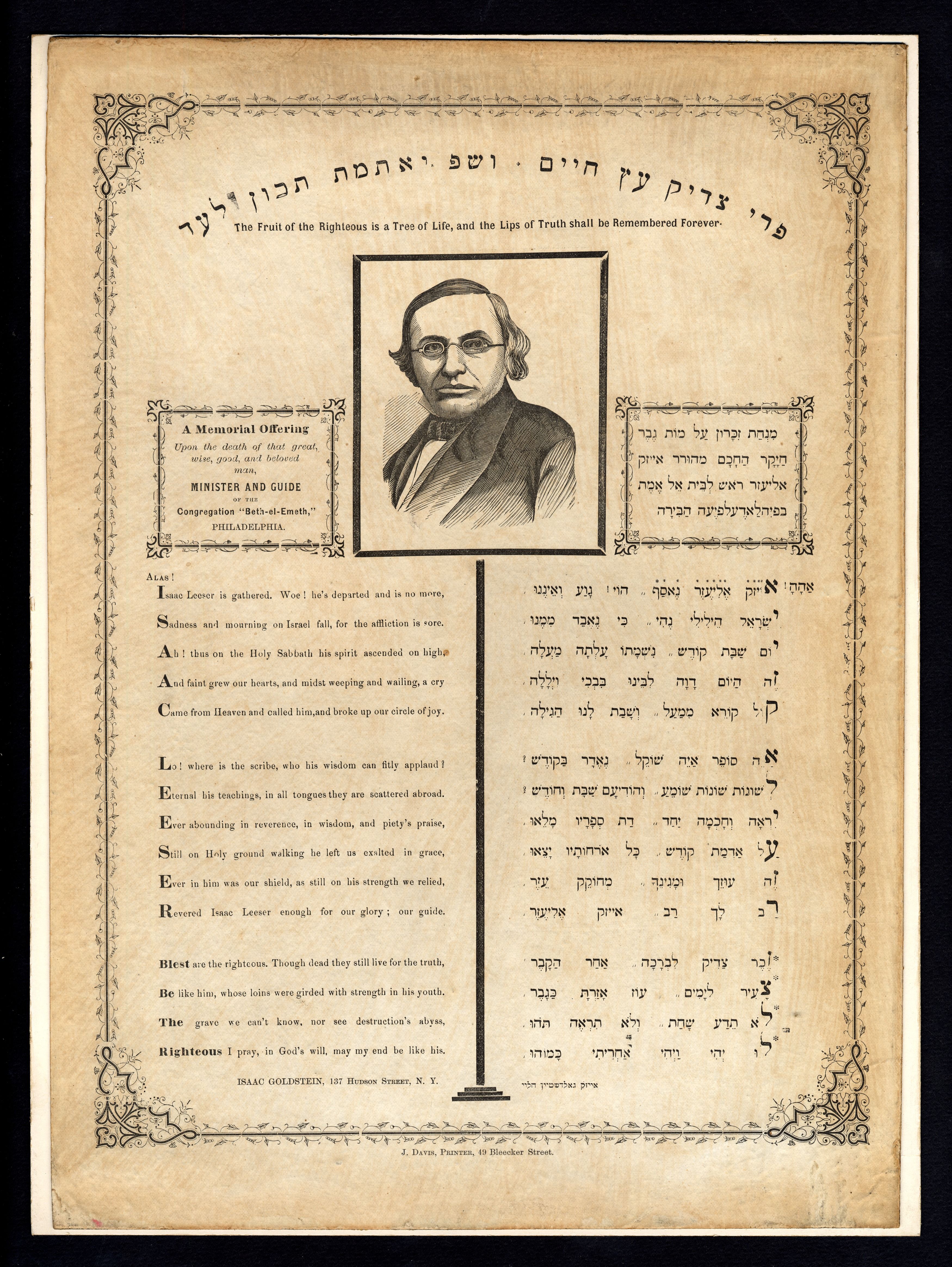

ISAAC LEESER.

SIVAN 5616, JUNE 1856.

Hebrew

"To learn and to teach, to observe and to do."

June 17th 1886.

Dr. ?

Opinion

˶whether post-mortem examinations,

under any circumstances, should

be allowed in Jew's Hospitals.˶

The Occident, a monthly periodical

devoted to the diffusion of knowledge

on Jewish Literature and religion

June 1856.

1.

At a meeting of the Directors of the Jew's Hospital held on the 14 of January last, the subject of post mortem examin_ation being under consideration, Messrs. the Rev. S. M. Isaacs, John I. Hart and T. J. Seixas were appointed a committee to correspond with the Rev. Dr. Adler, Chief Rabbi of London for the purpose of eliciting his opinion ˶whether post mortem examinations, under any circumstances, should be al_lowed in the Hospital." And at a meeting of the Board held on the 23rd of March, the Rev. S. M. Isaacs, Chairman of said committee, submitted a communication in reply, the consideration of which was deferred until the next meeting of the Board. At a meeting of the Directors held on the 6th of April, the consideration of post mortem examinations being resumed, it was on motion

Resolved, That in conformity with the letter of the Chief Rabbi Adler, of London, no post mortem

2.

examinations will be allowed in the Jew's Hos-pital, unless the same come under the excep-tions contained in said letter.

Resolved, also That the letter of Rev. Dr. Adler together with the forgoing resolution, be published in the Occident and Asmonean.

T. J. Seixas

New-York, Rosh-Chodesh Nissan, —April 7th 5616.

3.

Office of Chief Rabbi, London, February 26th 5616.

To the Committee of the Board

of Directors of the Jews' Hospital, New-York.

Gentlemen: I have the honor, herewith, to acknow-ledge the receipt of your esteemed favor of the 6th of Shevat, Ult.; and, whilst thanking you for the confidence you have been pleased to repose in me, I can not refrain from expressing my deep appreciation of the firm attachment to our most ancient law, so nobly evinced in your above mentioned communication. In com_pliance with your wishes, I shall forthwith pro_ceed to enter at some length into the question, for the clear development of which, it will be requisite to direct your attention to the three undermentioned principles:

I. Our religion enjoins most strictly the necessity of burying the dead in a respectful manner.

II Our Religion teaches that a certain degree of sanctity be attached to the lifeless remains

4

of a human body; and

III As a natural consequence of these two principles, our religion forbids every kind of maiming and desecration of the dead.

I. ˶Our religion enjoins the necessity of burying the dead in a respectful manner." This may be proved from the following facts:

1. Throughout the Bible, the burial of historical characters is specially recorded.

2. The want of burial is considered as a terrible calamity. (Isaiah XIV 19.20; Psalms LXXIX 3; Ecclesiastes VI 3.)

3. Decent burial is sufficiently important to be promised as a reward for good actions (1 Kings XIV 13.)

The oral law likewise repeatedly dwells on the great necessity of decent interment, de-clares that the burial of an exposed corpse supersedes all other precepts, and considers every person engaged in burial, as being en-gaged in a most important duty.

5

Although both the Bible and oral law speak of burning, in connexion with deceased kings, yet that burning does not refer to the corpse, which was uniformly buried, but to valuable articles which were burnt in honor of the dead. That this is the true meaning, may be proved from the considerations:

1. Both in the Bible and in the oral law the word Hebrew, when used in reference to the above mentioned custom, is never followed by the accusative sign Hebrew, but by the particles Hebrew or Hebrew denoting "concerning" "for" (vide Jeremiah XXXIV, 5; 2 Chronicles XVI. 14, ibid. xxi 19; Talmud Abodah Zorah, fol. 11., Joreh-Deah, cap. 348).

2, The Talmud (ibid.) and Joreh-Deah (ibid.) express-ly mention what articles were burnt.

3, The matter is, however, put beyond doubt by this verse, (2 Chronicles xvi 14) ˶and they buried him in his own sepulchre;....and they made a very great burning for him" This needs no farther comment.

6.

II ˶Our religion teaches that a certain degree of sanctity be attached to the lifeless remains of a human body˶ The proofs of this are:—

1. The Divine command not to permit the corpse, even of the a criminal, to be exposed over night.

2 The wish which was expressed to be buried close to a prophet. (1. Kings XIII. 28-31.)

3. The restoration to life of the corpse which touched the body of Elisha (2 Kings XIII. 21.)

4 The great reverence felt towards the burying place of ancestors. (Nehem. II. 3-5.)

The oral law also forbids delay in burial, unless it be fore the purpose of preparing a more dignified funeral; and strictly commands that the funeral should be solemnized with be-coming marks of respect to the Departed. (Vide Moed Katan, fol. 27; Joreh Deah, cap. 343.

III ˶As a natural consequence of these two prin-ciples, our religion forbids every kind of maiming, and of Desecration of the dead."

The desecration thus prohibited is of three kinds:—

7

1st The appropriation of any portion of the corpse for purposes of gain, or private use of any kind. This is prohibited, Yaddim IV. 6; Sanhedr. fol. 47, 48, Chulin, fol. 122; Niddah 55a; Yorah Deah, Chap. 349.

2nd Disinterment likewise prohibited. Baba Bathrah, fol. 154; Abel Rabbathi, IV. 12; Joreh-Deah cap. 363; Chosen-Mishpat, cap. 235, §13.

3rd Post mortem examinations, also prohibited (Chulin fol. 11.b;-Joreh-Deah, cap. 403, §6.) except in cases wherein the life of a human being depends on such examination; as, for instance, when anyone is accused of having murdered the deceased, and a post mortem examination is required for the purpose of investigating the charge, or when the nature of the disease is unknown, and there is another patient affected with the same malady,—then a post mortem examination is permitted, in order to save the life of the survivor: these however, are only the rare exceptions. But as a general rule, post mortem examinations is con-sidered by our law as desecration, and prohibited. It may be urged, on the other side, that the progress

8

of medical science renders a certain amount of post mortem examination unavoidable; but to this I reply, that since such treatment of the Decea-sed is a desecration, it can only be permitted in cases of extreme necessity; and even if some exceptions must be made, the poor ought not to be the victims. You would surely not embitter the sweetness of charity by such hardship, and not allow that the feelings of the poor man, when necessity compels him to seek shelter in your Hospital, be harrowed on his death bed by knowing that he must pay, even with his body, for the hos-pitality of your roof; and it is hardly necessary to describe to you the agonizing pangs of the near relatives, who can not protect their dear departed ones from that desecration which they view with the greatest horror. Thus humanity forbids us from making an exception in cases of the poor; and you know that the oral law, in several places, enjoins that, in our treatment of the Dead, we ought to make no distinction whatever between

9.

the rich and the poor. The only exceptions which either reason or humanity can admit, are crimi-nals who had committed high crimes.

From the above, I trust that it will be clear to you, that religion and humanity unite also here in declaring that post mortem examinations should not be permitted in the hospital.

With the assurance that I shall be ever ready to afford to you any information you may require in the matter, and praying for your prosperity and spiritual welfare,

I have the honor to be Gentlemen, yours faithfully,

N. Adler Dr.

10.

Although neither connected connected with the medical profession, nor disposed to view the dissection of the human body with any degree of pleasurable interest, nor advo-cating post mortem examinations generally, whether of those dying in a Hospital or at home, whether ˶high or low, rich or poor," all of which circumstances appear, however, quite irrelevant to the present inquiry, I would simply ask: ˶Does the mosaic Religion in-terdict such examinations?˶ In a communica-tion, lately received from the Chief Rabbi Adler, of London, are arguments which, with due deference to so learned an authority, I cannot admit; and I would like to have stronger reasons and proofs adduced, before acknow-ledging that our religion prohibits an in-vestigation, which is purely for the benefit of the human race.

The Rev. gentleman commences by laying down three principles or propositions

11.

The first that ˶Our Religion enjoins burial of the dead in a respectful manner;˶ to this I fully assent. Second, That ˶our religion attaches a certain degree of sanctity to the lifeless remains of a human body; for argument's sake let this be allowed. And, as a natural consequence of these two principles we may admit the deduction that our religion forbids every kind of desecration of the dead. But I cannot concede that the dead can be maimed, or that a post mortem examination is either a maiming or a desecration of the dead, any more than a surgical operation is a desecration of the living. In the former case, the intention is to benefit millions living, and yet to live; in the latter, the primary object is individual good only. The revd. Dr. endeavors to prove that a degree of sanctity is attaches to the remains of a human body, and cites a few incidents from the scriptures to establish it; but if they are the strongest that can be ad-duced, I think the second principle is not so

12.

clearly proved, i. e. of there being a degree of sanctity (i. e. holiness and purity) attached, etc as for the wish to be buried close to a Prophet, (1. Kings, XIII 28-31.) the desire was not expressed because it was "a dead body", but on account of the sanctity (holiness and purity) attached to the character of the Prophet. Regarding the resto-ration to life of the corpse which touched the body of Elisha, (2 Kings XIII.21) I can not perceive how, or in what manner, that miracle signifies a degree of sanctity attached to human remains generally. It appears to me, as though the fact of his being a Prophet, only, produced the miracle, unless it be claimed that any other body would have caused the same.

The doctor for this informs us what is considered desecration. First, the appropriation of any portion of the corpse for purposes of gain, or private use; in this I fully concur. As to disinterment, I beg to differ with the learned gentleman, and the author,ities he cites. There are numerous circumstances under

13.

which disinterment is the reverse of desecration; but as this is irrelevant at present to the point at issue, I will not farther pursue it.

I have always believed that what was not for-bidden in the laws of Moses we might do, provided such things were not against reason or nature; and farther that the spirit of those Laws make it an imperative duty, to do that which will benefit our fellow-creatures; and it cannot be denied that post mortem examinations are made with that humane end in view. But the exceptions in the Doctors communication would limit post mortem investigation to the examination only of a person suspected to have been killed by foul means. For, as to the exception made, when the nature of a disease is unknown, what mortal physician can affirm that another patient is affected with the same? Thus the second exception amounts almost to prohibition.

The Doctor adds, as apparently his own opinion, that ˶since a post mortem examination is a desecration,

14

it can only be permitted in cases of extreme necessity, and that the only exceptions which reason and humanity can admit, are criminals, who had committed high crimes." The latitude given to the words ˶extreme necessity," not being defined, I am unable to construe this portion of the Reverend gentleman's reply. Regarding ˶reason and humanity," I think it can be clearly proved they both unite in sanctioning any effort to progress in a knowledge so useful and practical as surgical science. And from what I have read in the Doctors com-munication, I cannot see wherein religion prohibits it.

As to individual feelings and prejudices which are not confined to any particular position in life, whether affluent or otherwise, I (individually) would conform to the wishes of the Deceased, if such had been expressed, or to those of his family; but all this is quite foreign to the question. We have nothing to do with personal prejudices and

15

family feelings, or the wealth or poverty of the parties, or as to the place in which they die. The simple question to decide is, does the letter or the spirit of the laws of Moses forbid post mortem examinations, when such will throw light upon science, and ultimately benefit the human race?

As for the opinions of ancient Rabbins on the subject, we are not obliged to receive them as infallible and decisive: Their opinions are not more entitled to consideration than those of the Rabbins and learned me of our own day, who, by the general advance of knowledge, are perhaps better constituted to ˶shew us the sentence of judgment;" and to them we are referred in ˶all matters of controversy within our gates." (Vide Deuteronomy, XVII. 8-9.).

16.

To S. Abrahams M. D. New-York.

My dear friend! About four years have elapsed since I enjoyed the pleasure of a literary communication from you. I received no direct news from you, and was satisfied to learn from other sources of your well-being. I exclaimed with cicero, si vales, bene est, ego valeo. But meeting with one of your productions in the Asmonean, a fiew few weeks ago, engaged as you are, in a controversy on an important question, I resolved to break my silence and to address these lines to you.

I perfectly agree with you, my dear friend, in the opinion that Dissection is by no means contrary to our oral law; nay, I do even maintain that our sages and ancient teachers practised themselves anatomical investigations. For, how could they otherwise have aquired that knowledge of the structure of the human frame which they so frequently display in the Talmud and Zohar? How else could they have asserted

17

so positively that the human body consists of 248 members in contradiction to the wise men of other nations, some of whom assert that their number is only 245, while others count 249, others 256, and some even 266 members?

I will now cite, for the satisfaction of your oppo-nent, several passages from the Talmud and Zohar, and then ask him how our sages could speak scientifically of a thing of which they could have no idea, how they could infer one proposition from another, if they were not allowed to convince themselves of the correctness of their inferences? How could they, for instance say with such precision and positiveness: Hebrew?

It is generally known that the word brain is a collective term which signifies those four princi-pal parts of the nervous system exclusive of the nerves themselves, which are contained within the cranium; they are: the cerebrum or the larger part.

18.

the cerebellum or little brain, the pons variolii which is the connexion between the two hemispheres of the cerebellum, and the medulla oblongata. Varoly is known as the first who thus described our brain; but we find already in the Zohar the following Hebrew. Another passage of the Zohar reads thus: Hebrew Hebrew.

The heart of an adult person consists of four muscular cavities, namely, the two auricles (or attria) which their two auricula cordis and two ventricles, which are respectively named from their position right and left. The right auricle and right ventricle form together the right part and the left auricle together with the left ventricle form together the left part of the heart. In the Zohar, section Behar, we read as follows: Hebrew Hebrew Hebrew. Of the auricula cordis we read in

19

the Zohar, section Behar, Hebrew Hebrew. The Zohar, section Pinchas, tells us of the lungs, that they send the inhaled fresh air to the heart, whence it spreads over all the blood-vessells, tempering their heat, which might else injure the body. Hebrew Hebrew Hebrew Hebrew.

Of the amniotic liquor we read in the Talmud, Niddah, fol. 28, as follows: Hebrew Hebrew. Zohar, adza Rabbah fol. 136 describes the skull as follows: The skull or cranium has three holes or sockets wherein the brains are imbedded; the brain is covered and protected by two membranes, the one is firm and strong, (Suramates;*) the other (pia mater,) thin and tender. Three parts of the brain diffuse themselves through thirty-two nerves all over the body

*So named from supposition that it was the source of all fibrous membranes of the body.

20

and spreads through all its parts;* Hebrew Hebrew Hebrew Hebrew Hebrew. You will admit that the three main organs with their thirty-two nerves, which are so systematically distributed, giving sensation and motion to the entire animal organism of life could not be more distinctly described.

We find also mentioned in the Talmud several surgical operations and experiments, as also, amputations of important limbs; for instance, in Aboda-Zarah, where an account is given of an operation for the cure of a fistula. In Talmud Yebamoth, fol. 75, it is stated that Mur Bar Rab Ashi, who is so frequently mentioned in the Talmud, had operated on a person suffering from a Hebrew.

Even the two great operations in op obstetrics, the

*The arachnoid, the third membrane of the brain, was probably not known to them at this time.

21.

Histerotonia Hebrew and Gastrotonia, Hebrew Hebrew were not unknown to the Talmudists. The first was deemed inadmissible on living women, probably on account of its being very apt to cause a permanent injury. The Hebrew or Lechtio Ceguraa, was mainly performed on a corpse, where the child could be born only by incision. Tossephoth Abodah-Zarah, fol. 10. states on the authority of Josephus, that this operation gave birth to Julius Caesar, and was for that reason called caesar Hebrew Hebrew Hebrew. Niddah fol. 30., reports of a dissection made on two female slaves of Queen Cleopatra. Hebrew Hebrew During twenty centuries vain attempts have been made to discover when the vivication of the embryo takes place; but all

22.

remained in darkness; the mystery could not be solved. Hypocrates assigned the sixth day; Haller the fifteenth till lately Prevost and Dumas after many experiments on animals, have fixed the third as the right day; and will it not strike everyone with surprise that in the Talmud we find the same opinion laid down? Hebrew Hebrew.

Another difficult matter on which physiologists have long disputed, and was lately set at rest by the celebrated French Physician, Dr. Valep Velpeau, was already clearly under-stood by the Talmudists fifteen hundred years ago (Hebrew) Hebrew. The theory of De Graaf, or the doctrine of the ovules, now so generally adopted, is also embraced in the Talmud, in Niddah fol. 31. as follows: Hebrew Hebrew.

I believe to have adduced sufficient proofs;

23.

but I could cite ten times more if required, showing that the men of the Talmud possessed a knowledge of the interior as well as the exterior structure of the human body, which they could never have acquired without dissecting, and without anatomical investigations of their own; and there is no passage known to me, which could, in the least, justify the presumption that the Jewish physician ever made any distinction between the body of an Israelite or a non-Israelite, in this respect; and therefore I conincide with you in the opinion that dissecting is not only not pro-hibited to the Jewish surgeon, but that it is right that he should not neglect any opportunity where he can enter the secret laboratory of nature in order to scrutinize her working within, and understand her symptoms from without. Very respectfully, your friend

Dr. B. Illowy St. Louis April 6. 5616.

American Israelite October 22 1896.

THE JEWISH LAW ON POST MOR-

TEM DISSECTIONS.

[For the ISRAELITE.]

A gentleman in the far West lately requested to be informed through the ISRAELITE whether the Jewish Law prohibits a post mortem dissection for the purpose of a medical investigation.

This question was occasioned by an occurrence in a hospital where a Jewish man died of a peculiar kidney dis-ease the nature of which the physi-cians were anxious to ascertain by an autopsy. To this, however, the rela-tives strongly objected stating that the Jewish religion prohibits any mu-tilation of the dead body of a human being.

In answer, I would say that a want-on mutilation of a human body would certainly be against the spirit of the Jewish law which ordained that even the corpse of the executed criminal shall be protected against a disgrace-ful exhibition (Deut. xxi, 23). But whether it is permitted or prohibited to perform a dissection of the dead for the purpose of ascertaining the cause, seat or nature of a disease—such a question was entirely foreign to the Biblical antiquity. In the Book of Judges xix, 29, the dissection of the dead body of an outraged woman is mentioned, but this was for a different purpose and concerned an extraordi-nary case from which no conclusions can be made for the question before us

That dissections of corpses were per-formed in an early time of the rabbi-nical period is evident from the con-siderable anatomical knowledge which the Mishna teachers displayed in stat-ing almost exactly the number of bones and of sinews in the human body and in each of its limbs (See Mishna Ohaloth I, 8). Of the disci-ples of Rabbi Ishmael (in the second century C. E.) it is expressly stated in the Talmud (Bechoroth 45a) that they prepared the corpse of an execut-ed criminal, for the purpose of an anatomical investigation. A Jewish physician by name Theodosius who flourished in Palestine in the second century is reported (in the Tosephta Ohaloth ch. iv.) as having been so skillful in the science of anatomy that, on a certain occasion and in the presence of other physicians, he proved to be able to select from a basket full of human bones those belonging to each other and in this way reconstruct the original skeletons.

While thus the Palestinean authori-ties of the Mishna period seemed to have had no objection to dissecting corpses for necessary purposes. Rabbi Cahana one of the Babylonian Amora-im of the fourth century remarked incidentally in a discussion of the law that dissecting a dead body was a dis-grace, adding however that for the purpose of saving a human life in a judicial investigation it ought to be permitted. (Chullin 11b.)

Although the rabbinical codes of the Middle Ages contain no express prohibition against dissections, such an act was generally held to be con-trary to the regard due to the dead.

The celebrated Rabbi Ezekiel Lan-dau in Prague, flourishing in the second part of the last century, dis-cusses in one of his responses (Noda Bihuda, second collection, Yore Dea, No. 210) the question whether it was permitted to dissect a body in or-der to determine the nature of the disease that caused death so as to know how to treat it under similar symp-toms. As was to be expected of this Rabbi who though very distinguished in rabbinical lore strongly opposed secular studies, his answer was not wholly in favor of the medical science. He decided that such a dissection was only permitted when it immediately could serve to heal a patient who is just suffering of a similar disease, but it was not allowed when it should merely serve to enrich medical science to possibly heal a similar case at some future day.

A modern Rabbi will hardly make such a subtile distinction but, when asked for his opinion, allow a dissec-tion or an autopsy whenever it is very desirable in the interest of medical science and of suffering humanity.

DR. M. MIELZINER, Prof. Hebrew Union College.

The above text refers to Occident Volume 14 No. 4 pages 131 through 136. Click here to view. - Identifier

- LSKAP20-1062

- Date

- 1856-06-17

Part of The Occident, And American Jewish Advocate, 1856

Isaac Leeser, “The Occident, And American Jewish Advocate, 1856”, 1856-06-17, Isaac Leeser Digital Repository, accessed September 16, 2024, https://judaicadhpenn.org/legacyprojects/s/leeser/item/69349